Vegetal Ontology

Plant sentience is often dismissed as its characteristics cannot easily be overlaid on the signs of consciousness expressed in human, or animal, subjects. A philosophical consideration of vegetal life requires an expanded appreciation for modes of being peculiar to plants, attending to them on their own terms as centres of intelligence that exert behaviour within scales of time and movement that differ vastly from our own. If the animal is bounded by a body that moves, the plant is instead defined in ‘being-sessile’; rooted in one place and subject to change and growth in a complex and highly sophisticated relationship with its environment.

F. Percy Smith, Minute Bodies: The Intimate World of F Percy Smith, 2016, directed by Stuart Staples. Film Still. Copyright unknown

F. Percy Smith, Minute Bodies: The Intimate World of F Percy Smith, 2016, directed by Stuart Staples. Film Still. Copyright unknown

F. Percy Smith, Minute Bodies: The Intimate World of F Percy Smith, 2016, directed by Stuart Staples. Film Still. Copyright unknown

F. Percy Smith, Minute Bodies: The Intimate World of F Percy Smith, 2016, directed by Stuart Staples. Film Still. Copyright unknown

We now know that plants can learn from experience and environmental stimuli; that they can interact and communicate, not just with other plants but with other animals and insects in highly manipulative ways; and their sensitive, rhizomatic root structure and decentred, collective intelligence provides a far more modern way of thinking about social and environmental relations. To be sessile, embedded in a milieu, is to express life-force on a molecular-cellular level. Plants do not possess a neurological centre but, like art perhaps, they are defined by a state of ceaseless unfolding, a material knowledge or thinking without thinking, and an insatiable, immanent becoming.

Michael Marder

Michael Marder is one of the foremost voices in Vegetal Ontology. His work, which spans Phenomenology, Environmental Philosophy and Plant Thinking, has contributed to the reappraisal of vegetal life in continental philosophy, acknowledging both the ubiquity and alterity of plants as beings with their own subjectivity - one that is radically different to our own.

Marder is Research Professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of the Basque Country in Spain. Amongst his numerous titles on plant being are The Chernobyl Herbarium in which he collaborated with Anaïs Tondeur to meditate on pioneer plants that have taken root on the site of the nuclear disaster. In his 2014 work, The Philosopher's Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium, Marder approaches the western philosophical tradition from the humble vantage of vegetal life, connecting the ideas of its prominent figures to particular plant genera: Plato to the plane tree; Hegel with the grape vine; Irigaray and the water lily. Here we share an abridged version of his chapter on Plotinus.

The Philosopher's Plant 3.0: Plotinus’ Anonymous ‘Great Plant’

January 4, 2013

Plotinus did not just philosophise; he led a philosophical life. If we are to trust his most illustrious student, Porphyry, his existence was scrupulously self-effacing.

Plotinus did not celebrate his own birthday but offered sacrifices on the birthdays of the long-dead Socrates and Plato. He did not wish his portrait to be painted, as he reckoned the body to be a worthless image of the soul, and its artistically produced likeness — an image of an image. And, to top things off, he seemed to be ashamed of being in the body, praising instead the virtues of the soul.

A thinker of the unity of the One, Plotinus succeeded like no other philosopher to combine the teaching of the pre-Socratic Parmenides with Platonism and Aristotelianism in the six books of his magnum opus, the Enneads, edited and compiled by the same faithful disciple, Porphyry.

There is no better point of entry into Plotinian philosophy than the allegory of the world — permeated by what he calls “the Soul of All” — as a single plant, one gigantic tree, on which we alongside all other living beings (and even inorganic entities, such as stones) are offshoots, branches, twigs, and leaves.

The idea of an overarching soul was certainly not new at that point: Plato’s Timaeus, for one, presented the universe as an enormous animal. What was groundbreaking was imagining the universal soul as a plant.

“Why does Plotinus descend from an animal to a tree image?” you will ask. Is it because in the plant the One and its fragmentation into the many coexist without leading to a blatant contradiction? Is it because this fantasy frees Plotinus to think of the One outside the organismic model and the typically animal ways of moving and living?

Although the portrait of the world as plant is painted most vividly in Book IV of the Enneads, its details are scattered through the rest of the treatise and shore up the most basic points of Plotinus’ philosophical argument. Significantly, the world-plant does not belong to any recognizable genus or species. It is one of a kind, precisely, because it is a depiction of the One. Its anonymity coincides with its uniqueness, the uniqueness of the non-classifiable origin and unity of a system of classification prior to its branching out.

If there were a genus “world-plant,” it would contain but a single example, which would overlap with the general category that lends it a name. (Of course, this observation is true unless we subscribe to the string theory of contemporary physics, with its hypothesis of multiple parallel universes. Assuming an infinite number of possible worlds, the genus “world-plant” would come to accommodate innumerable examples of vegetable totalities.)

In and of itself, the world-plant is a useful theoretical fiction. In it, “the Soul of the All,” as Plotinus imagines it:

(that is, its lowest part) would be like the soul of a great growing plant, which directs the plant without effort or noise; our lower part would be as if there were maggots in a rotten part of the plant — for that is what the ensouled body is like in the All. The rest of our soul, which is of the same nature as the higher parts of the universal soul, would be like a gardener concerned about the maggots in the plant and anxiously caring for it (Plotinus, Ennead IV.3.4, 25-35).

The Soul of All may envelop everything that exists, but it is not undifferentiated in itself. Plotinus translates the Platonic division between “the highest” and the “lowest” into a separation between “the great growing plant,” which is the ensouled body of the entire world, and a gardener who cares for it and who represents the soul in its pure state, unmixed with the corrupting bodily dimension.

Now, if a living body corresponds to the rotten part of the plant, we can begin to understand the reasons behind Plotinus’ shame in the face of his own embodiment: seeing death as a moment of liberation, he craved a return to the blessed condition of the gardener, his soul cleansed of its material incarnation. While many Christian authors, including St. Augustine, took this as a reference to the congenital sinfulness of corporeality, or the inevitable fallenness of the soul trapped in a body, Friedrich Nietzsche will have brushed away the Plotinian metaphysical daydream as nihilistic.

The tremendous implication of Plotinus’ vegetal portrait of the world is that there is nothing outside the soul, which always and necessarily cares for itself. There is, on the contrary, something of the plant in the gardener and something of the gardener in the plant.

The Socratic dictum that “all soul cares for the soulless” no longer applies there where a pure, because “unmixed,” soul nurtures its impure counterpart trapped in the dark cavern of the body. Even such inanimate things as rocks are not formless, as they exhibit crude material forms that are the pale reflections of the soul’s own formative capacity.

And so it is with the gardener, who does not shape raw matter but cares for the pre-formed plant, the spontaneous, effortless, and noiseless growth of which should be, as much as possible, protected and redirected away from the deadly activity of the maggots, symbolizing the self-forgetting of the soul in the body. As far as Plotinus is concerned, then, all pure soul cares for the embodied soul, so as to reduce the dependence of the latter on corporeality and hence to defend the soul from evil, symbolized by its “fall” into matter.

From the image of the world as a plant we learn about the nature of the One. Plotinus likens the One to:

the life of a huge plant, which goes through the whole of it while its origin remains and is not dispersed over the whole, since it is, as it were, firmly settled in the root. So this origin gives to the plant its whole life in its multiplicity, but remains itself not multiple but the origin of multiple life” (Plotinus, Ennead III.8.10, 5-15.)

Life, to be sure, is multiplicity and dispersion; it is lived, always and everywhere, in the plural as lives. Yet, Plotinus implies, when we concentrate on living creatures, we are only seeing the upper segments of the world-plant with its intricate branching out at the tips. We literally miss the forest for the trees.

A more radical vision, on the other hand, aims at the radicle, the source, or the root of life that is always one and the same, unaffected by the dispersion of the living. As a vegetal elaboration on the Aristotelian “unmoved mover,” the ever-living root of the One, which is not split into the many, animates all finite lives without being in the least affected by their changeability or, indeed, finitude. It is an exceptional root that does not grow and that, remaining self-identical, upholds the origin’s unviolability.

The root of the world-plant becomes, in Plotinus’ philosophy, the yardstick for measuring the worth of multiplicities comprising this world. As a rule of thumb, the closer a branch is to the root, the firmer its grasp on being, which it vicariously imbibes from this principle of growth. As for the tips of the branches, the leaves, and even the fruit, many of these are so distant from the root that they neglect their provenance from the One.

That is how the possibility of contention and conflict arises where unity and peace should, in principle, prevail. The One starts to wage a war against itself the moment its most distal parts grow oblivious to their common emanation from the same root and, in an illusion of independence, assert themselves at the expense of other tree limbs, branches, and twigs. The closer these parts identify with matter, which is thoroughly divisible, the more they violate the absolute wholeness of the One.

Breaking out into finite lives ruled by the merciless cycles of growth and decay, the One is no longer (simply) one, even if its static root is appointed to serve as the guardian of unity. That is why Plotinus abandons the animal metaphor and resorts to the plant, where the One and the not-One meet without negating one another.

The Rebirth of Nature

Rupert Sheldrake

Rupert Sheldrake is a biologist and plant physiologist whose long-term research into the development of plants led to his pioneering theory of morphic resonance. In this recent talk, Sheldrake traces the progression of scientific thought back to its origins in the mysticism of ancient Greece, in which natural philosophy imbued all material phenomena with spirit. He describes its development through the Cartesian split of mind and matter in the 17th century and the establishment of a mechanist world view in the western enlightenment, to more contemporary discoveries in quantum physics that are returning us to a unified awareness of the natural world as animated and alive – including the stars, planets, oceans, mountains, rivers and lakes - heralding a new era in intellectual, social and cultural life.

Nicholas William Johnson

Caterpillarage, 2018. Acrylic, pigment, and fabric on canvas. 145 x 185

Nicholas William Johnson’s work implies the presence of an organising principle or logic inherent in plant life, contesting the view that plants lack their own agency, and delineating that agency as something fundamentally strange to us. He explores the notion of plant-as-actor through formal patterned arrays of botany and with paraedolia, the arrangement of forms in such a way that suggests a countenance, or a face, or a subtle sentience in nonhuman lifeforms. In his list of Further Reading, selected especially for The Botanical Mind, he charts the strands of thinking that inform his practice, situating plants as an alternate mode of consciousness.

Fruit Fl-eyes, 2020. Acrylic, pigment, and fabric on canvas. 80 x 65 cm

ARRAY, 2020. Acrylic, pigment, and fabric on canvas. 80 x 65 cm

Further Reading

REFERENCE WORKS

Botany has shifted historically from taxonomy to gene sequencing and along the way many strands of thinking about plants have emerged in accord with other ideas.

In Praise of Plants by Francis Hallé (1999) examines plant morphology and growth patterns and their implications further afield. He finds analogues in crystallography by physicists, the mathematics of fractal branching patterns and their space filling tendencies, the architecture of corals, or tree ‘crown-shyness’ as an indication of a mechanism of awareness of self and other in plants. Primarily Hallé’s book examines anthropocentric and zoo-morphic biases in botany, that plants unfold increasing their surface area for example, whereas animals do the same by a process of infolding. Hallé examines the decentred nature of plant life which is quite alien to concepts of the individual and sexuality.

Ethnobotany, the ethnographic study of plants, concerns the relationships between plants and humans, as with the rubber trees studied in the Amazon by the botanist Richard Evans Schultes. His study of these trees inevitably bound him to the many tribes that live in the Amazon and their endless knowledge of the vast network of flora there. Schultes is the pioneer of modern ethnobotany best known for his work cataloguing the many medicinal plants used by the indigenous people of the Amazon. His works often take the form of an herbal, which describe the plants botanically, their chemical analyses and active compounds. Ethnobotany also takes the form of anthropology cataloguing the attendant uses, rituals, myths and cultures surrounding plant life. Compendium of Symbolic and Ritual Plants in Europe (1999), is an exhaustive reference of the way European plants have played a part in the religious experiences of humans.

SOME EXPEDITIONS / HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS

The names of plants can be tidy, cryptic parcels of information and history. Knowing the names of plants often means tracing their histories and symbolisms. A species of Brugmansia volcanicola was named, for example, by RE Schultes because he discovered it on the slopes of the Paucé volcano (One River, Wade Davis, 1996). Plant names also change with histories and cultures. Banisteriopsis, was first named telepathine, because of the alleged telepathic inducing powers of the plant – later changed to caapi an indigenous name for the vine when the alkaloid in question was determined to have already been isolated elsewhere. That plants and their properties are known to us at all is because of the people who have lived with and used them – ritualistically, medicinally, agriculturally – and those intrepid enough to go looking for them. A Wizard of the Upper Amazon tells the

extraordinary tale of Manuel Córdova-Rios a mestizo from Iquitos, Peru, who was captured as a boy on a rubber trapping expedition and raised by them as a vegetalista. In the forward, Dr. Andrew Weil speculates that the, ‘ability to share consciousness through the medium of the visual imagination must be a capacity of the human nervous system … The visual cortex is implicated … What we see when our visual cortex is interpreting signals from somewhere other than the retina might have more to tell us about the nature of reality’. Archaeologists have called this sort of imagery entoptic phenomena. The Signs of All Times Times (Lewis-William, et al. 1988) is an academic paper of anthropology and archaeology which argues that palaeolithic art can be analysed using a neuropsychological model of the apprehension of entoptic (interior) imagery in three stages of plant induced altered consciousness with reference to form-constants in nature and the structure of the visual cortex. These form constants are also echoed in plant forms, and suggests something more about the nature of reality, an underlying thread perhaps connecting the mechanics of perception with the growth patterns in other life forms.

PLANT THINKING / ANTHROPOLOGY, THEORY AND PHILOSOPHY

In roughly the last twenty years a broad school of thought has emerged called ‘the ontological turn’ or the ‘nonhuman turn’ in anthropology, ethnography, philosophy, and theory. In anthropology Philippe Descolar (Beyond Nature and Culture, 2005) considers the ways humans have lived and live, alongside plants and animals and recontextualises the western world view in the context of ‘multi-species ethnography’. How Forests Think (Eduardo Kohn, 2013) builds on 25 years studying with the Runa in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Kohn’s claim that forests think, is about forms of thought – forms of representation – beyond language.

There is a trend here towards dismantling old anthropocentric models of thought and classification towards something decentred, ecological, environmental – the rhizomatic as opposed to an arboreal model of knowledge (Deleuze & Guattari) and the companion-species and cyborgs of Donna Haraway. Jane Bennett in an essay on Object Oriented Ontology says “the nonhuman turn can be understood as a continuation of earlier attempts to depict a world populated not by active subjects and passive objects but by lively and essentially interactive materials, by bodies human and nonhuman.” (The Nonhuman Turn, Ed. Grusin 2015). She cites poet Walt Whitman as an example, and Spinoza. Especially so in this decade there has been a windfall of thought on this subject. Michael Marder is an important proponent. Following a raft of scientific papers on the subject, in ‘Plant-Signalling

and Behaviour’ (vol. 7:11, Nov 2012) Marder outlines the ‘phenomenological framework of plant intelligence’. His books and work develop the philosophical model of plant intelligence in opposition to old western metaphysics.

THE LANDSCAPE AS ACTOR / FICTION esp. SCI FI

Hybridity, symbiosis, loss of control, erasure of the boundaries of self, expansion of consciousness in the vast network of the natural world we are all already enmeshed within, all of these ideas are explored in these science-fiction stories and the more recently demarcated genre called the ‘New Weird’. ‘Plant consciousness’ is a theme that has occasionally been the subject of speculative fiction, especially, e.g., in the compendiums of Ann and Jeff VanderMeer and his own stories, where plants or plant-like lifeforms often hybridise and transform humans, decentralising their bodies and dissolving boundaries we traditionally ascribe to individual life-forms. In The Southern Reach Trilogy (2014) a biologist inhales a spore of a lifeform she is observing and gradually has to accept her role as an unreliable narrator, no longer detached from the landscape she is observing.

Often these fictions describe a transition – or mirroring – between the interior mental states of their protagonists and the exterior world of plant life or landscape and their rhizomatic or fungal networks of ‘consciousness’. In Vaster than Empires and More Slow, Ursula K. Le Guin (1975) writes about the merging of planetary vegetal consciousness and an empathic alien. Hothouse, by Brian Aldiss (1962) a story of a continent-spanning banyan tree, plants with nervous systems, and a symbiotic, knowledge bearing morel fungus. In JG Ballard and Margaret Atwood there have been fusions of interior states and exterior landscapes (The Crystal World, Ballard 1966 & Death by Landscape, Atwood, 1991). Alan More’s comic series Swamp Thing is a cult deviation on these ideas, grandiose passages of imagery and prose propose the union of a human and plant and eventually intergalactic consciousness. In the obscure, quite beautiful film, Silver Heads, by Yvgent Yufit, (1999) Soviet scientists design an experiment to form a synthesis of human and tree DNA, which needless to say results in increasingly irrational behaviour and integral psychological contradictions in the subjects. Vegetable life perhaps is more difficult to master.

All words by Nicholas William Johnson

Richard Evans Schultes on a cliff in the Vaupés. Published in Wade Davis, The Last Amazon: The Pioneering Expeditions of Richard Evans Schultes, 2016

A young person of the Kamëntsá people with the blossom of culebra borrachera, Sibundoy Valley, Colombia, June, 1953. Photo RE Schultes

The Three Halves of Ino Moxo by César Calvo, Translated by Kenneth Symington, published by Inner Traditions International and Bear & Company, ©1995. All rights reserved.

Illustration from Francis Hallé, In Praise of Plants, 1999

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Compendium of Symbolic and Ritual Plants in Europe. Marcel de Cleene & Marie Claire Lejeune. 2002.

In Praise of Plants. Francis Hallé.1999.

Patterns in Nature. Peter S. Stevens. 1974.

Fungipedia. Lawrence Millman. 2019.

Entangled Life. Merlin Sheldrake. 2020.

Vine of the Soul. RE Schultes & Robert Raffauf. 1992.

Plants of the Gods. RE Schultes, Albert Hofmann & Christian Rätsch. 1974, Revised 1992.

Ayahuasca Reader. Editors Luis Eduardo Luna & Stephen F. White. 2000.

Rainforest Medicine: Preserving Indigenous Science and Biodiversity in the Upper Amazon. Jonathan Miller Weisenberger. 2013.

Pharmakognosis. Dale Pendell. 2010.

One River. Wade Davis. 1996.

The Lost Amazon. Wade Davis. 2016.

A Wizard of the Upper Amazon. Frank Bruce Lamb. 1986.

The Three Halves of Ino Moxo. Cesar Calvo. 1995.

Amazon Beaming. Petru Popescu. 1991.

‘The Signs of All Times: Entoptic Phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic Art’, JD Lewis-Williams & TA Dowson in Current Anthropology. 1988 Apr; 29(2)

A General Theory of Magic. Marcel Mauss. 1902.

Beyond Nature and Culture. Philippe Descolar. 2013.

How Forests Think. Eduardo Kohn. 2013.

The Nonhuman Turn. Ed. Richard Grusin. 2015.

‘Plant intentionality and the phenomenological framework of plant intelligence’. Michael Marder, in Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2012 Nov; 7(11).

Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life. Michael Marder. 2013.

Vibrant Matter. Jane Bennett. 2010.

The Antipodes of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience. Benny Shannon. 2002.

The Southern Reach Triology. Jeff Vandermeer. 2014.

Death by Landscape. Margaret Atwood, in Wilderness Tips. 1991.

Vaster than Empires and More Slow. Ursula K. Le Guin, in The Wind’s Twelve Quarters. 1975.

The Crystal World. JG Ballard. 1966.

Hothouse. Brian Aldiss. 1962.

The Saga of the Swamp Thing. Alan Moore. 1984-1987.

Silver Heads. Film by Yevgeny Yufit. 1998.

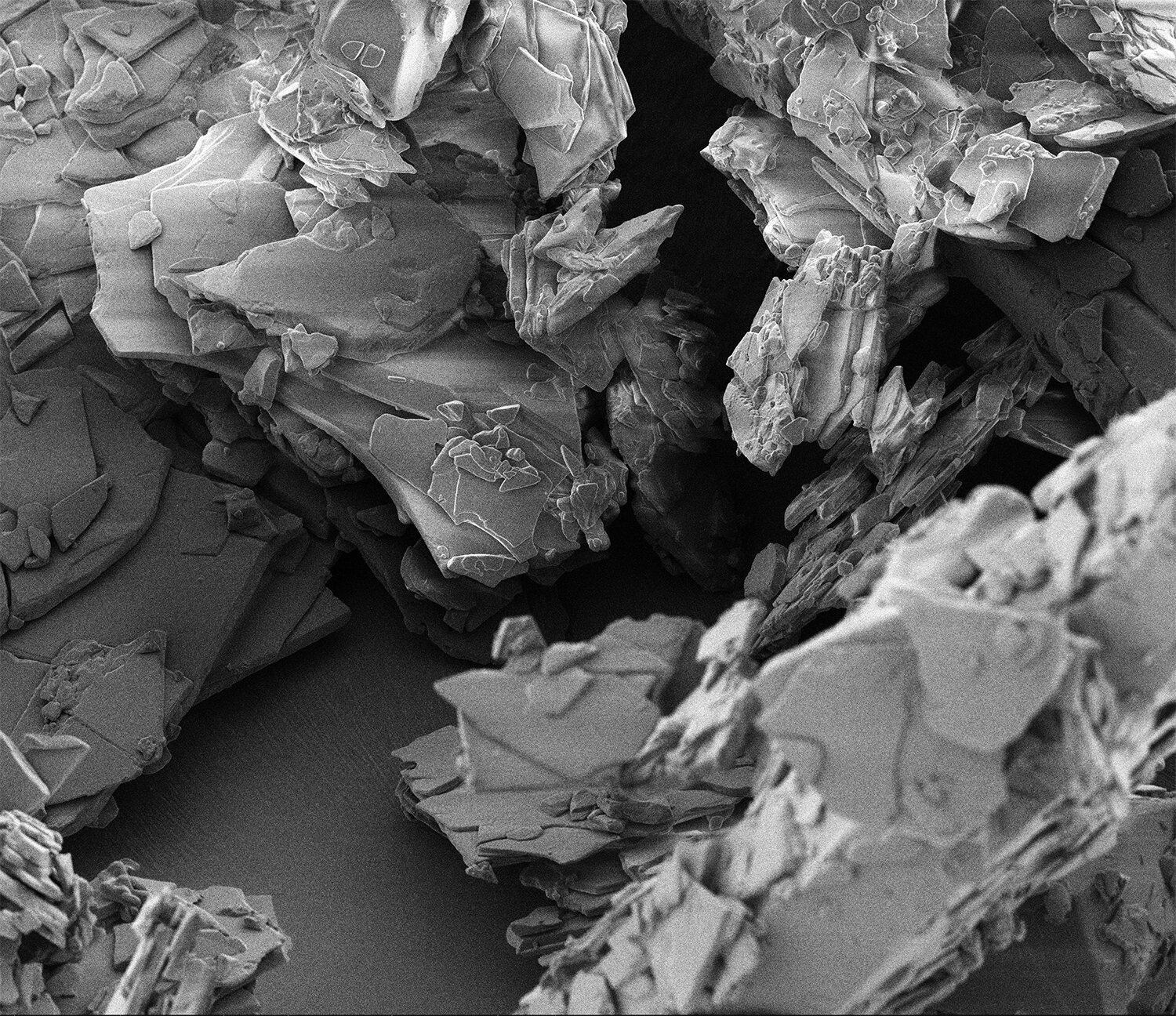

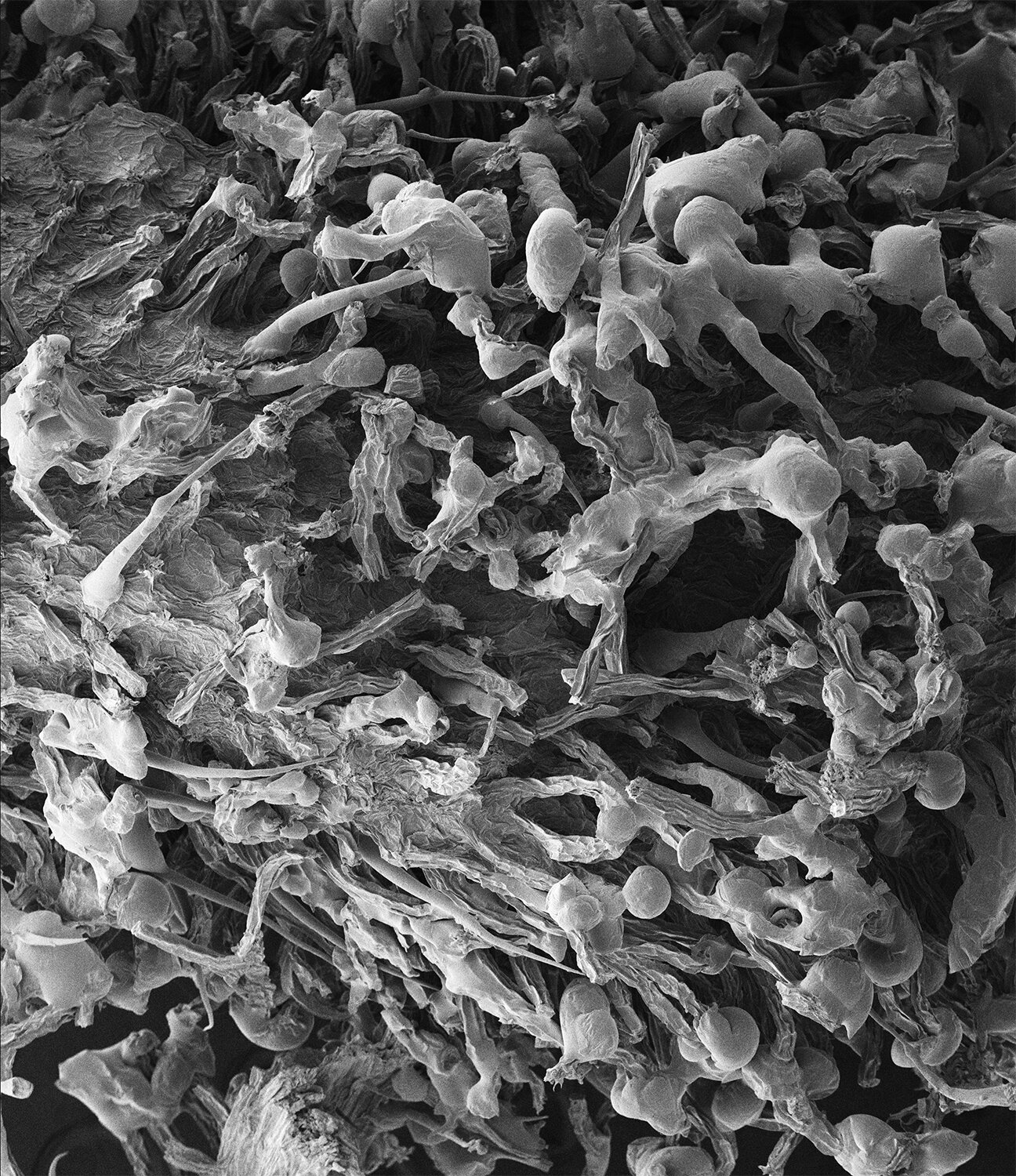

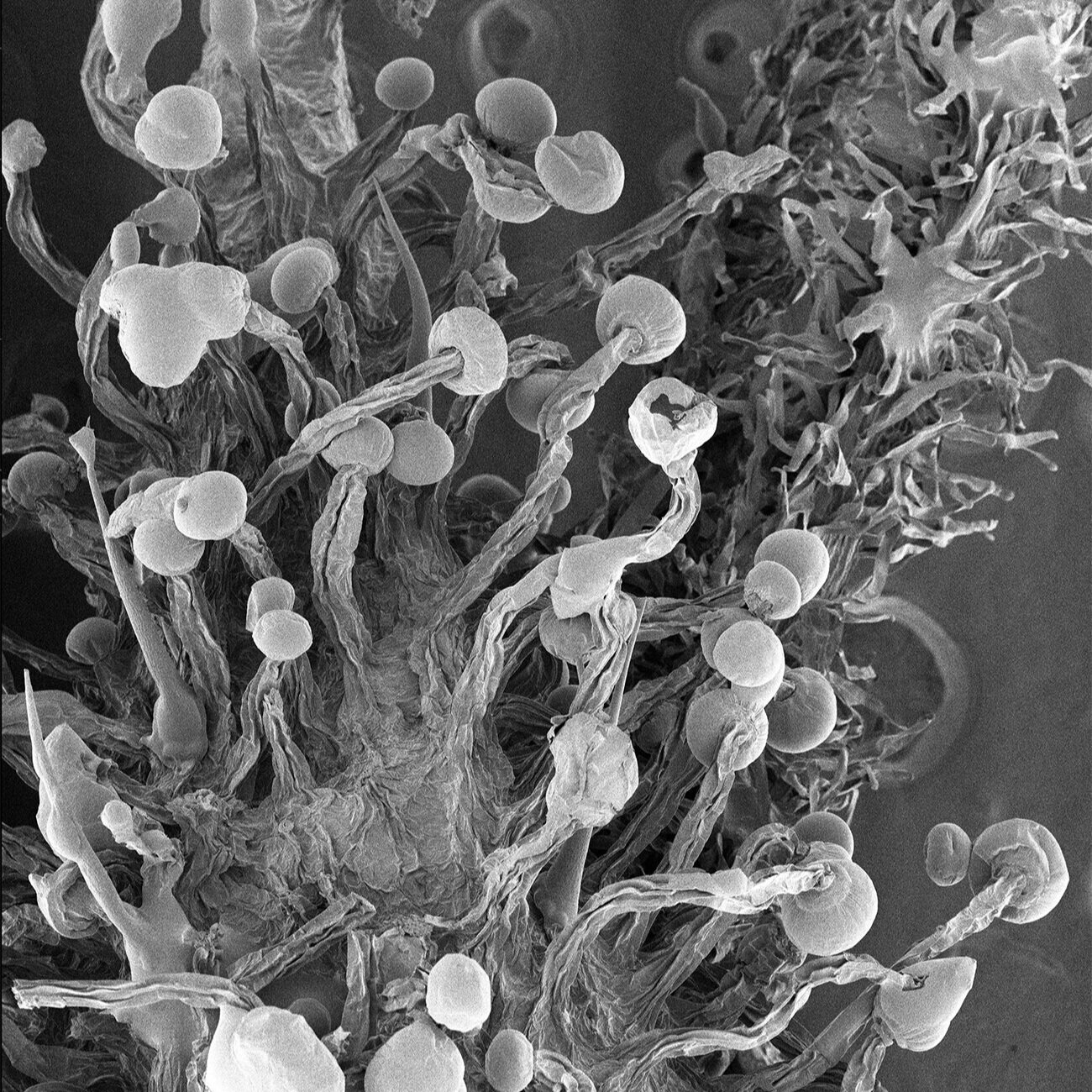

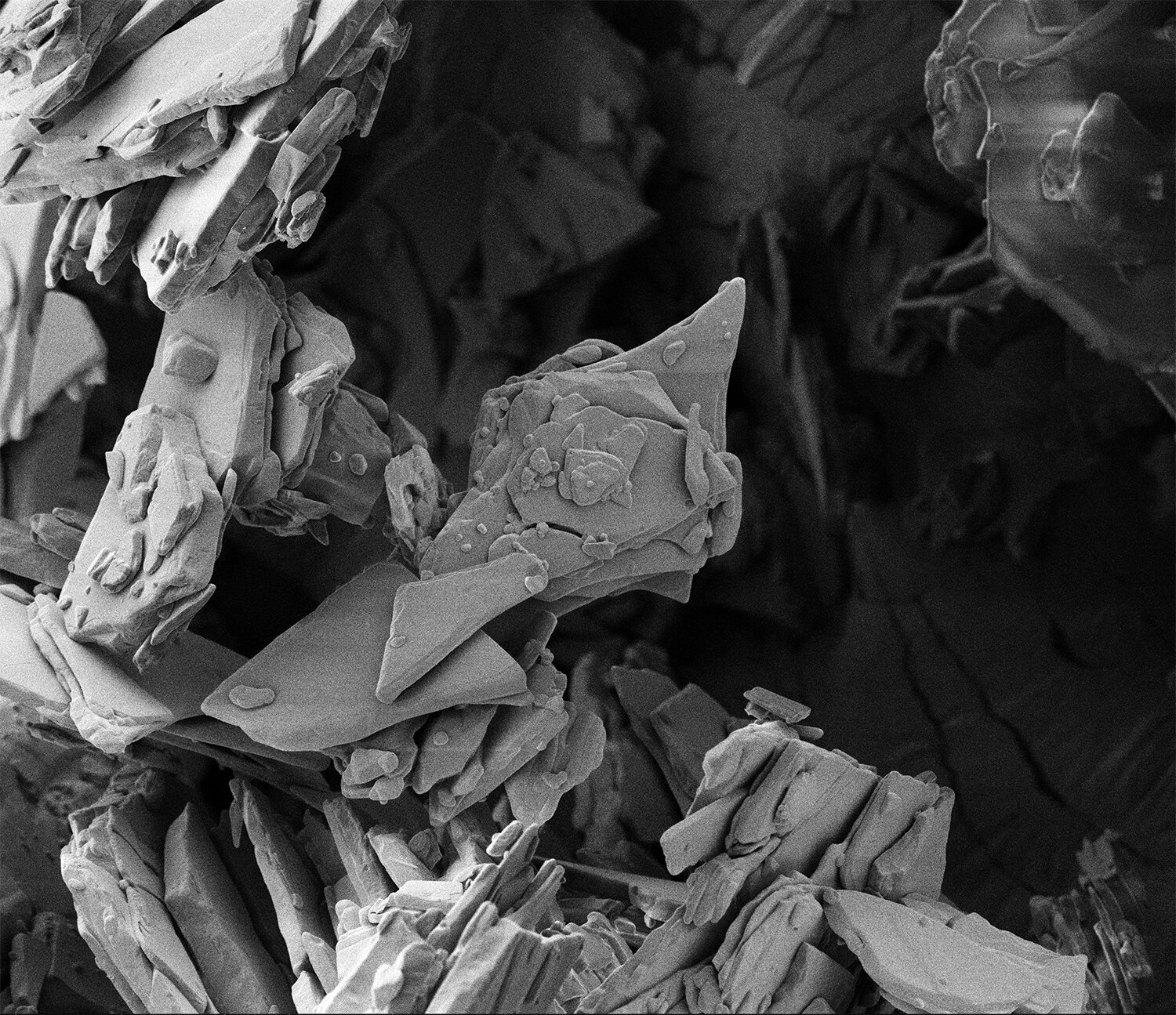

Joachim Koester

This new series of photographs by Joachim Koester reveals an associative morphology of worlds and structures hidden beneath the surface of two widely- used-plant-derived stimulants: cocaine alkaloids and cannabis plants. The images are made using SEM technology – a microscope that uses a focused beam of electrons to scan surfaces, offer a glimpse into the histories and present production economies of these two plant substances.

Left to right, top to bottom: Joachim Koester, Untitled (cocaine #6), 2019. Silver Gelatin Print; Joachim Koester, Untitled (cannabis #4), 2019. Silver Gelatin Print; Joachim Koester, Untitled (cannabis #3), 2019. Silver Gelatin Print; Joachim Koester, Untitled (cocaine #2), 2019, Silver Gelatin Print. All images courtesy the artist and Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen. Courtesy the artist and Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen

Detail from: Hortus Sanitatis, 1491. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Photo: Laurie Auchterlonie/Wellcome collection

Female Mandrake. Detail from: Hortus Sanitatis, 1491. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Photo: Laurie Auchterlonie/Wellcome collection

Gemma Anderson with

Wakefield Lab and John Dupré

Gemma Anderson’s experimental drawings emerge from an iterative process of (mis-) understanding and reforming in her longstanding collaboration with a biologist (James Wakefield) and a philosopher of science (John Dupré). Following Goethe, they share the question of how to create mental and physical images of living processes without adopting a ‘thing/object’ based vision. They understand living systems as ‘processual’ - as patterns and eddies in a flow rather than static, solid objects in a machine. Anderson’s images represent major processes in living organisms as scores for an orchestra or choreographies of elements working together in a dance reflecting on the shared qualities of pattern and waves of energy.

Anderson is an artist and researcher, currently co-investigator on the art/science/philosophy AHRC funded project ‘Representing Biology as Process’ (2017-2020) at the University of Exeter.

Gemma Anderson, Garden of forking paths (series); Mitosis Score, spiralling spindles, 2019. Pencil, watercolour and colour pencil on paper, 31 x 41 cm. Courtesy the artist

Gemma Anderson, Garden of forking paths (series); Mitosis Score, spiralling spindles, 2019. Pencil, watercolour and colour pencil on paper, 31 x 41 cm. Courtesy the artist

These drawings make visible aspects of dynamic living processes such as cell division and protein folding (cross species) at the molecular and nano scale. Rather than describing morphological characteristics, the abstract content of the drawings aligns to energetic relationships and movement patterns. They are made in collaboration with cell and molecular scientists and a philosopher of biology as part of an ongoing research project 'Representing Biology as Process' www.probioart.uk

Relational Process Drawing, Gemma Anderson, 2020

‘Relational process drawing’ focuses on the dynamic patterns of life and draws together relationships between energy, time, movement and environment. The molecular, cellular and organismal can be understood as ‘nested processes’ – for example, protein folding is essential to cell division (mitosis), which is essential to plant growth - each process intrinsically related to many others and engaged through reciprocity. Different domains of the plant, for instance, signal different amounts of cell division by modifying protein folding.

This is only a start to reconfigure the many more related processes that act and interact during plant development. The holobiont integrates the life cycles of many organisms into a collective organism with a unified physiology. The tree is a common example. Imagination, visualisation and collaborative drawing with scientists reveals how a new epistemology can begin to ‘make visible’ a processual and relational view of life.

Soil, John Dupré and Gemma Anderson

The four elements of antiquity, earth, air, fire and water, look a motley bunch from the viewpoint of modern science. Air, we would now say, is at least mainly a mixture of elements (nitrogen and oxygen), give or take a few greenhouse gases. Water is a compound, but at least a more or less homogeneous one. Fire is a true outlier, being not a stuff at all but a relatively simple process, oxidative combustion. Earth is an outlier of a rather different kind, to which I shall turn.

Putting fire on one side, we might more charitably say that the remaining elements, earth, water and air, gesture towards the full spectrum of stuffs, in the sense philosophers contrast with things, providing paradigms for the phases of matter, respectively, solid, liquid and gas. But whereas air and water are not only relatively simple stuffs, but also by far the most abundant representatives of their phases, nothing like this can be said of earth. There are many abundant solids on our planet—many kinds of rock, the sand that covers vast areas of desert, and finally, the main topic of this brief essay, soil or, as it is often called “earth”.

The point of this little journey into ancient scientific thought is that soil, even to this day, is often thought of in much the same way as air and water, as a relatively simple stuff. It is of great importance as the medium in which plants, the ultimate source of all our food, grow. But it is still sometimes imagined that its role in the nurture of plants is little more than providing a support to keep them upright, and as a vessel for holding the nutrients that they require to grow. Whether or not anyone explicitly holds such a view, it is a view implicit in industrial farming. The stuff is churned up (ploughed) annually to provide a clean homogeneous medium for the planting of seeds, and then doused with industrially produced chemicals to provide the plants’ nutrition.

But in reality, soil is an extraordinarily complex system, or as I prefer to say, process. The error in the simple view just sketched is most bleakly displayed by the calculations of soil

experts that on current methods of industrial farming we have about 60 harvests left before the whole system is dead.

So what is this process, soil? It is a process because its persistence, which is to say its survival as a medium actually capable of nurturing plants, depends on cycles of mutually stabilising and sustaining interactions between a huge variety of organisms, and their joint maintenance of the structure and constitution of healthy soil. These organisms include, first, countless kinds of bacteria—literally countless as we have yet to produce a technology capable of distinguishing the different kinds that coexist in any quantity of soil. While we can estimate that a teaspoonful of soil contains up to a billion individual bacterial cells, we cannot properly sort them into a particular set of kinds. And this is in part because the genetic constituents of bacteria are constantly in transit between individual cells, so that the kinds of cells present, as defined by their genetics, are themselves in constant flux. This flux makes possible the presence of microbes with the appropriate genetically encoded functions at any point in the system.

Second are the fungi which exist as a massive network of threads, or mycelia penetrating the roots of plants, and spreading through the surrounding soil. The more familiar but sporadic mushrooms are merely the spore-bearing fruiting bodies of this more persistent and fundamental symbiotic system. As has recently been discovered, this mycelial web can actually connect plants to one another, even plants of different species, thus creating a community of plants capable of sharing or exchanging nutrients.

And finally of course, there are the plants themselves, not merely resting in the soil, but contributing to the ongoing healthy state of the soil. In particular, plant roots contribute to one of the most vital features of soil, its structure. The arrangement of the physical particles of soil into more or less compact components of various sizes,

and with more or less spaces between particles to facilitate the circulation of air, water, and nutrients has a decisive influence on the ability of soil to sustain plant growth.

This structure is dynamically maintained, by the growth and decay of plant roots, by the movement of earthworms, carrying organic matter into the soil which, in turn, stimulates biological activity, and even by microbial activity. It is even likely that a properly functioning network of channels within the soil facilitates movement of bacteria, and thus access to the range of genetic resources that exist within the wider microbial community.

Various aspects of industrial farming can do long term damage to soil and soil structure. Heavy machinery compacts the soil, reducing the channels through which air and water circulate. Monocultures greatly reduce biological diversity at the microbial as well as at the level of plants and animals, and this can reduce the stability of the soil system and its resilience in the face of various shocks. Ploughing allows heavy rains to wash away soil, including all its various living residents. And ploughing also destroys the mycelial webs reducing their functionality.

In short, soil is an astonishingly complex living system, a process sustained by the interactions of vast numbers of large and small organisms, and in principle capable of persisting as long as appropriate use and management maintain the various components of the system. Treating it, as a finite resource to be used up rather than stably maintained as, in effect, occurs in much contemporary large-scale agricultural land use, is a potential disaster for the sustainability of the human food supply. Dead soil will neither keep the plants upright nor provide them with the nutrients they require.

Gemma Anderson and John Dupré

Gemma Anderson and John Dupré

Gemma Anderson and John Dupré

Gemma Anderson and John Dupré

Gemma Anderson

Observation and Operation: A Plant Meditation, 2020. Audio, 25 mins

During the process of observation it becomes apparent that individual plants are sites of many forms and symmetries; each body begins to reveal itself as yet another composite: a landscape of form. Plants can have isomorphic relationships in their internal workings and composition; therefore, individual plants are sites of composition, and some parts of the plant seem more important because they gesture out towards resemblance with other plants. With a collection of plants, it is helpful to then identify two or more plants that share a form or resemble each other. This meditation is a practice to develop novel plant imagery in the ‘mind’s eye’. Here we focus on a plant, but you could also try this with another material. The practise may lead to a drawing or a piece of writing or something else. It lasts around 25 minutes. You can repeat the stages or pause to vary the timings of the practise. It will probably help to close your eyes, although sometimes gestures and drawings in the air will help. Select which exercises are right for you.

P.J.F. Turpin, The Plant Archetype published in Goethe, Works on Natural History, 1837

Gemma Anderson is an artist and researcher based at the University of Exeter. Together with John Dupré, author of numerous titles on the philosophy of science, and James Wakefield, a cell-biologist, she is investigating novel image-making practices to provide more intuitively dynamic representations of living systems through an innovative collaboration between art, biology and philosophy.

For more information please visit: http://www.probioart.uk/