Sacred Geometry

Echoing the fractal and spiral geometries inherent in plant-forms and flowers – as well as the psychoactive visions induced by (entheogenic) mind-manifesting plant medicines – certain patterns or designs emerge again and again in art and science, appearing and reappearing across cultures and through time. Blueprints for the natural world, they seem to connect the macro- to the micro-cosmos, revealing an encoded intelligence.

These ‘sacred’ geometries can be seen in the arrangement of Camelia and Dahlia petals, the seeds in a sunflower head or the fractals of Romanesco broccoli. They recur throughout nature in the animal, mineral and vegetal kingdoms – the curve of a conch shell resembles the unfurling of a fern, or the spiral of a lizard’s tail. The flower-like figure of the mandala, common to Indian, Japanese, Persian, Mesoamerican and European religions, is one of the oldest spiritual symbols and another example of these sacred geometries. As too, is the proliferation of pattern and repetition found across Islamic, Nordic and Neolithic art. As Theophrastus wrote in the 2nd Century BC: ‘Repetition is the essence of the plant’ – a life of unceasing nourishment, growth, replication, and a complex and constant extrapolation of forms.

Ernst Haeckel, Peromedusae, 1904. Lithograph plate from Art Forms of Nature. Public Domain

Rupert Sheldrake

Why is there so much beauty in the world?

Rupert Sheldrake is a biologist and plant physiologist whose long-term research into the development of plants led to his pioneering theory of morphic resonance. In 2017 he gave this talk to an audience on Cortes Island, Canada BC, exploring how the sense of beauty has evolved, concluding that it is an inherent quality of nature including the human mind.

Sheldrake argues that beauty is a pervasive and unifying principle – one that drives the continuation of life and accounts for why we are able to recognise aesthetic qualities at all. Flowers evolved as a feature of vegetal life around a hundred million years ago and are amongst the life forms most celebrated by humans for their beauty. Darwin proposed that there would have been no flowers until there were eyes to appreciate them – designed by nature to attract mobile creatures to pollinate for them. The radial and bi-lateral symmetrical forms common to flowers are attractive not only to us, but to insects and birds as well, facilitating pollination, and pointing to a reproductive function – competition amongst sexual rivals.

In this talk, Sheldrake explains how there is a resonance between the thing perceived and the structure of the perceiving consciousness and that every phenomenon has a relationship to the whole of being; across an infinitely divergent spectrum there remain relations of the most intimate kind, of self-similarity, each part belonging to a higher-level whole; the holarchy. This idea accounts for the harmonic organisation of the universe, that allows the beings within it to be aware of the patterns and ordering principles underlying all things. Sheldrake explains that beauty exists in the phenomena we can see (flowers for example) and those we can’t without the aid of modern technology (galaxies through telescopes and organisms under microscopes) as well as the world we perceive in the modulations and rhythmic qualities of sound.

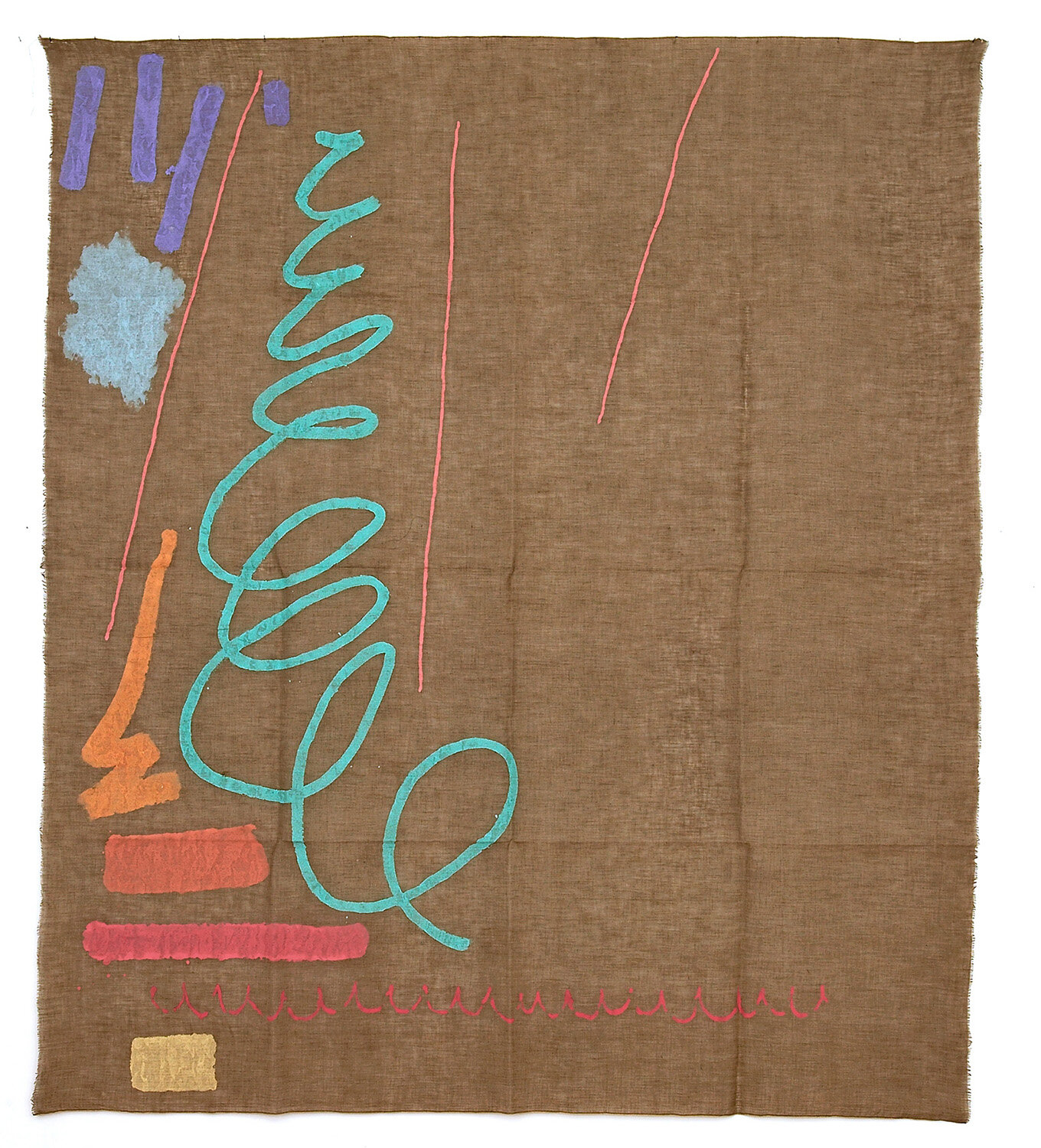

Philip Taaffe

Philip Taaffe’s paintings combine shapes and patterns emerging in the natural world with a lexicon of symbolic forms from diverse cultures including Arabic, Celtic, Pre-Colombian and Asian cultures. Sometimes calling on imagery from his own Irish-Celtic heritage, the motifs that populate his canvases are wide ranging, demonstrating the universal expression of patterns and symbols and in world religions and global cultures. Taaffe’s work seems to explore the animistic, mystical, magical and trance-like effects of forms, interrogating their motifs, penetrating into their structures and extrapolating them as patterns. Often combining plant, or other naturally derived forms, with cultural representations – the spiral geometries in fern fronds and shells with Nordic Viking ornament, and Roman architecture – the densely interwoven patterns express a subtle relationship between the organic, ornamental, pictorial and abstract.

Philip Taaffe, Lalibela Kabinett, 2008. © Philip Taaffe; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York. Photo: Matthias Langer

Read Robert Kelly’s poem, A Tangle for Philip Taaffee

Philip Taaffe, Large Viking Filigree Painting, 2008. © Philip Taaffe; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

Philip Taaffe, Painting with Teeth, 2002. © Philip Taaffe; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

Philip Taaffe, Cape Siren, 2008 © Philip Taaffe; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

Philip Taaffe, Calyptra, 2007. © Philip Taaffe; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

Peter Lamborn Wilson is a writer, poet and translator, who has written extensively on Islamic history, culture and society. In this essay, written for Philip Taaffe, he reflects on the ancient art of paper marbling, tracing a constellation of influences and associations that include hermetic guild mysteries, alchemy, Rosicrucianism, Athanasius Kircher, Paracelsus, and psychedelic visions. Describing nature’s language of forms as a dynamic system imbued with meaning, he identifies the mimetic signs found in artistic traditions ranging from the vegetal and crystalline forms of Islamic art and the Neolithic marks incised into sacred megaliths in Ireland, to the mystic cosmography and primordial chaos of Taoism that’s expressed in “grass” calligraphy.

Philip Taaffe, Interzonal Leaves, 2018. Mixed media on canvas, 283.7 x 212.6 cm. C Philip Taaffe, courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augusting, New York

Rosettes, saz leaves and carnations. North India, 17th Century. Mughal Voided Silk Velvet, 142 x 72 cm. Credit: Prahlad Bubbar, London

Anna Zemánková, Untitled c 1960. Crayon, pen on paper, 81 x 62.5 cm. Courtesy of The Museum of Everything

Anna Atkins, Cystoseira ericoides. From: Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions Volume I Cyanotype. Public Domain

Anna Haskel, Untitled, 1940. Pastel and pencil on paper, 30 x 22 cm. Courtesy of The Museum of Everything

Anna Zemánková, Untitled, c. 1960, Crayon, ballpoint ink on paper, 62.5 x 45 cm. Courtesy of The Museum of Everything

Anna Atkins, Sargassum plumosum. From: Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions Volume I Cyanotype. Public Domain

Anna Haskel, Untitled, 1940. Pastel and pencil on paper, 30 x 22 cm. Courtesy of The Museum of Everything

Kunstformen der Natur [Artforms of Nature], 1904) - organisms classified as Mycetozoa

Karl Blossfeldt, Plant Studies, Urformen der Kunst: Photographische Pflanzenbilder, 1928. Photograph, 31.2 × 24.2 cm. Public domain

Karl Blossfeldt, Plant Studies, Urformen der Kunst: Photographische Pflanzenbilder, 1928. Photograph, 31.2 × 24.2 cm. Public domain

Karl Blossfeldt, Plant Studies, Urformen der Kunst: Photographische Pflanzenbilder, 1928. Photograph, 31.2 × 24.2 cm. Public domain

Isomorphology, Gemma Anderson, 2013

Isomorphology is a comparative, drawing-based method of enquiry into the shared forms of animal, mineral and vegetable morphologies. As a holistic and visual approach to classification, Isomorphology runs parallel to scientific practice, while belonging to the domain of artistic creation. It is complementary to science, addressing relationships that are left out of the scientific classification of animal, vegetable and mineral morphologies.

Drawing is a process that can reveal the shared forms of conventionally unrelated species. The drawing process is intrinsic to the epistemological value of Isomorphology.

Gemma Anderson, Visual list of forms and symmetries of Isomorphology, a page from Isomorphology, 2013 (super-collider version, 2013, c Anderson)

Anderson, Gemma, 2012-2014, Hexagonal Forms, Isomorphology series, copper etching (>c< Anderson)

Natural History Museum Photographer (name), 2013. View of designated bench space for Isomorphology study in the Sackler Lab, Darwin Centre, The Natural History Museum. Photograph. (<c> Anderson)

“Life is anything but tedious owing to nature’s inexhaustible richness which... produces ever new, beautiful and fascinating forms that provide new material to speculate and ponder over, to draw and describe... in addition to the scientific element, it involves artistic matters to a large degree”

Ernst Haeckel

Giorgio Griffa

Giorgio Griffa’s minimal and primordial marks extend from his fascination with quantum energy, time-space mathematics, the golden ratio and the memory of visual experience since time immemorial. Believing in the ‘intelligence of painting’, Griffa allows the essential elements of his process, such as the type or width of the brush, the colour or dilution of the paint and the nature of the canvas, whether linen, cotton, hemp or jute, to influence and form the work.

The Great Circle

As within the hidden world, so without identity

Turin, May 3, 2020

Giorgio Griffa

It’s widely thought that there’s knowledge on the one hand (science, philosophy, mathematics), and the arts on the other (painting and sculpture, music, poetry), where the arts are an impenetrable mix of irrationality, madness, and elation, a placebo for all of life’s woes.

I don’t agree.

I believe instead that the arts, just like the sciences, are a pathway to knowledge—different in their methods and purposes, but it’s still all about knowledge.

Irrationality, madness, and elation are good means for probing that part of the world that the sciences are unable to penetrate. They’re similarly a product of reason, devised in this case to allow us to explore what lies beyond its boundaries.

Painting goes back to time immemorial, in my view well beyond the 35,000 years of the Chauvet Cave, back perhaps to the very dawn of homo sapiens. And I’m convinced of that not just because of the quality of the drawings in the Chauvet Cave, which bear witness to the existence of a mature language. What makes me think that it must have a very long history is the fact that painting gives visible evidence to the invisible processes of knowledge.

When we began to identify the components of the world—trees, animals, rivers, humans—what we began was the construction of a cultural world of ours that runs side by side the physical world, which is infinitely vaster, but without blending into it.

That duplication, of the phenomenon and the image of the phenomenon, lies at the origin of our knowledge and it’s what leads me to think that painting lies closer to that origin than any other form of knowledge, because it marks the very first step from the word that gives identity to the image representing that identity.

Painting goes hand in hand with the knowledge of its age. It tells us about the world by drawing on that knowledge, whatever it is… Ancient Egypt, Classical Greece, the Mayan world, the invention of writing. Painting tells us about the known world and about the unknown which we cannot identify; it explores the something extra the real world has over the cultural world.

And it tells us about another extra.

Our thoughts, the cultural world, are in turn a reality that adds to the natural world, in an immense circle without beginning or end. Our thinking investigates the world and by doing so enhances it, adding its realities, its ideas, words, and images. And painting enhances it even in a physical way through its presence, ever since its origins at least fifty thousand years ago.

The greatness of that phenomenon is matched by the paucity of our means and our energy, an insignificant detail when compared to the energy of the sun. So it’s no surprise that painting speaks through details, through the horses of the Chauvet Cave, Apollo and Daphne, Morandi’s bottles, Mondrian’s lines, kouroi, Hammurabi, Fujiyama.

It’s a part of the great circle, a minimal part, as is my own little game of words without identity, words which unlock for the shaman that hidden part of the world, which we cannot identify.

Giorgio Griffa, Verticale, 1977, 178 x 386 cm, acrylic canvas - work cycle: Segni primary

Giorgio Griffa, Tre linee con arabesco n.319 (A zio Henry - Matisse), 176 x 84 cm, acrylic on canvas - work cycle: Tre linee con arabesco, Alter ego

Giorgio Griffa, Veneziana, 1982, 300 x 260 cm, acrylic on canvas - work cycle: Alter ego

Giorgio Griffa, Sezione aurea 628 - obliquo, 2010, 245 x 620 cm, acrylic on canvas - work cycle: Canone aureo

Giorgio Griffa, Canone aureo 705 (VVG), 140 x 237 cm, acrylic on canvas - work cycle: Canone aureo, Alter ego

Detail - Giorgio Griffa, Canone aureo 203, Toskomt, Pieno vuoto, 2019, 206 x 400, acrylic on 3 canvases - work cycle: Canone aureo, Shaman, Dilemma

Giorgio Griffa, Undermilkwood (Dylan Thomas), 2019 - acrylic on 20 canvases, 200 x 650 cm (installation reference dimensions only) - work cycle: Trasparenze, Alter ego

All photos Giulio Caresio - courtesy Archivio Giorgio Griffa

ALL THE THOUGHTS OF ALL, a text by Giorgio about his work and practice

Next chapter

![Kunstformen der Natur [Artforms of Nature], 1904) - organisms classified as Mycetozoa](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e9ec61ef5f80d7b12d05328/1589277836868-ZK1LNWSV46HTVUO7N18G/Haeckel_Mycetozoa.jpg)